The farm was mixed, but increasingly important was our pedigree Hereford cattle herd. To properly record their pedigrees, we belonged to the Australian Hereford Society.

It was not surprising when the AHS contacted me through my father and offered me a job representing it on a shipment of mostly commercial Hereford cattle to Chile.

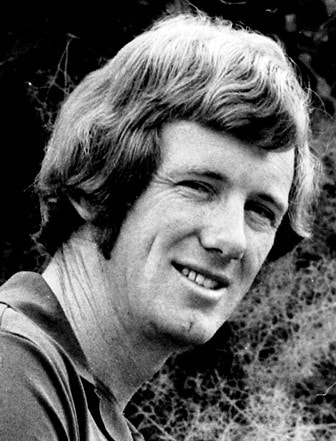

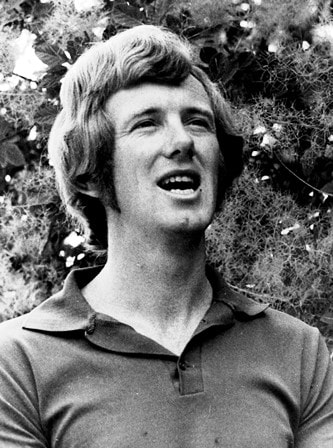

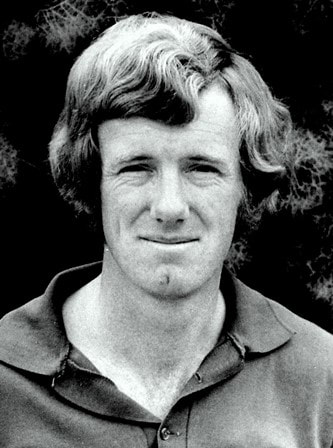

I quickly accepted and in June met Terry and John in Sydney, prior to joining a ship loaded with 650 pregnant Hereford females docked in Sydney Harbour. Terry and John, like me, were in their early 20s and had similar cattle raising experience. As well we would be looking after pedigree cattle which we would show and sell in Chile's capital Santiago.

The ship was loaded, and we departed to the east from Sydney. We were only two or three hours out of Sydney when the engines suddenly stopped. We were told it would have to be towed back to Sydney because the engine had seized.

It turned out that it had seized because, in a just completed overhaul, the engine's cylinders had been inadvertently chromed, forming a goo which stopped them.

The cylinder heads were removed and several men armed with angle grinders set to work removing the mass of chewed up chrome from the cylinder walls. It took about a week to remove. Meanwhile, we and the cattle remained on board.

With extra feed on board, we set sail again a week later and a week after that we passed between the north and south islands of New Zealand.

Quite suddenly the cattle started to calve and, because they were heifers, there were some birthing problems and some females and calves died.

We put this down initially to problems heifers often have giving birth the first time, but then discovered we had a problem with contaminated mixed feed. It turned out the feed was contaminated with bale hooks which are viciously spiked and curved bits of steel designed to hold the tops of bags closed. They were appearing in the feed bins and had been discovered in the stomachs and puncturing the hearts of some of the dead females.

A trickle of cows and calves continued to die until we reached the Chilean port of Concepcion about three weeks after leaving Sydney the second time.

While we and our pedigree cattle went by truck to the showground in the capital Santiago, the other 650 were trucked to various farms to be quarantined and injected with a foot and mouth vaccine.

There is no foot and mouth disease in Australia. Our policy is to kill infected cattle if it is found rather than try and treat it. But the Chilean authorities decided to use a locally produced vaccine to protect the imported cattle. Unfortunately, it didn't work well, and many cattle died.

Subsequently we used a well-regarded Argentinian foot and mouth vaccine on our pedigree cattle and successfully showed and sold them at the annual Santiago show that September.

The stock and station agent Dalgety and Co was handling the logistics of the shipment and, despite having an Australian representative in Santiago, did not seem to be getting the truth of what was going on.

So, I set out to correct the record, I think via an air letter to Sydney. Within a week I heard that the Australian boss of Dalgety was en route to Santiago to sort me out for the untruths I had seemingly expressed about the troubled voyage.

In any event, it was discovered that what I'd reported was at least largely true and the three of us continued on a relaxed and very pleasant exploration of Chile, Argentina and Peru.

...To be continued ...

David Palmer

July 2024

RSS Feed

RSS Feed