At that time, Peter MacCallum Clinic had an energetic Scotsman as head of the Physics Department. He was concerned at the possible fallout from the Maralinga tests, as strontium-90 was one of the by-products of atomic fission. It is sufficiently similar to calcium that any residual strontium can lodge in bones and possibly cause bone cancer. For Dr. Martin, that was enough data to make testing for fallout, even as far away as Melbourne, an appropriate project for a cancer clinic.

The workshop men at Peter Mac constructed a revolving arm on a four-legged stand and this was placed on the rooftop of the Little Lonsdale Street building. Cheesecloth ‘sails’ were clipped to the arm. A month or two later, a water collection was organized.

Each week, the cheesecloth needed to be replaced and the rainwater collected. This required going up in a lift three or four floors, a short set of stairs, out onto the roof and up a small ladder. No wonder I’d been given the job!

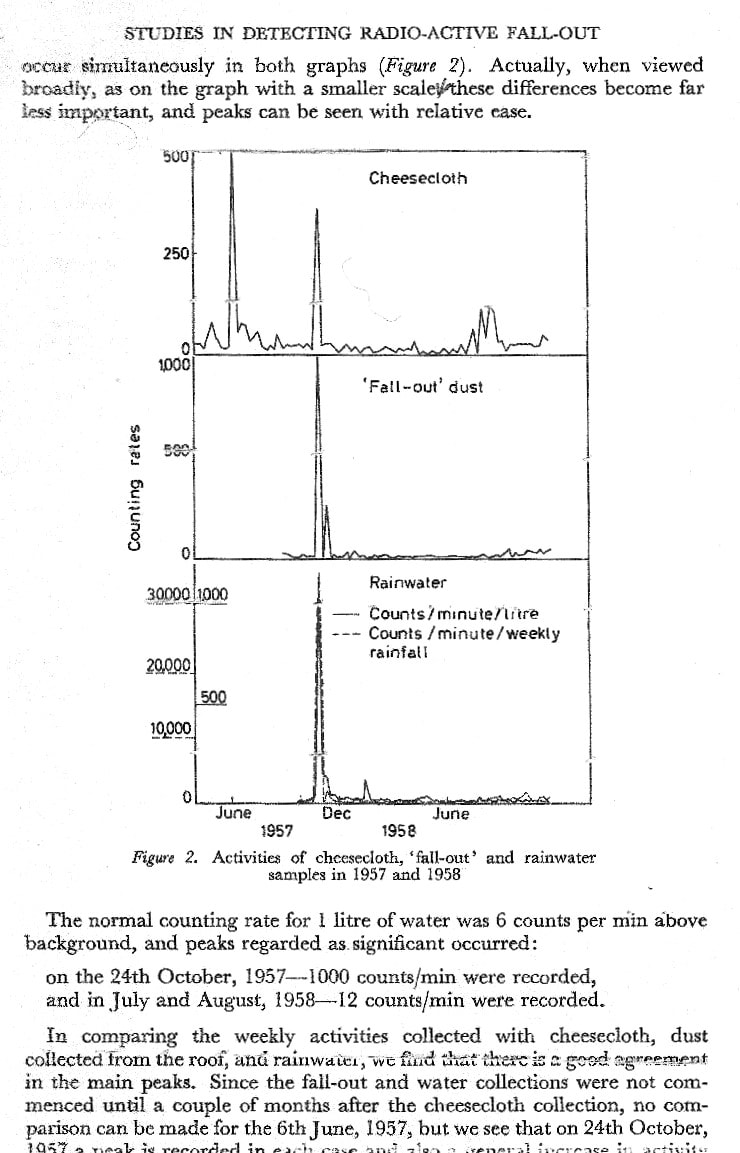

The results were significant. The background count for rainwater was 6 counts/minute. On the week ending 24th. October 1957, the measurement was 600 counts/minute. These peaks occurred two or three times, each time being about a fortnight after a test.

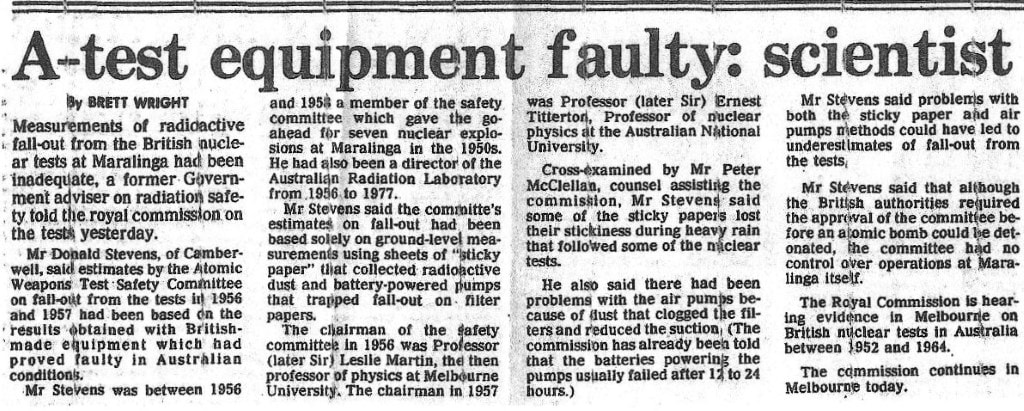

Twenty seven years later in 1984, an article appeared in ‘The Age’, headed

‘A-test equipment faulty’.

‘A former government advisor said that measurements of radio-active fallout at Maralinga had been inadequate. The fallout estimation had been based solely on ground level measurement using sheets of ‘sticky paper’ that collected radio-active dust and battery-powered pumps that trapped fallout in filter papers.

These could have led to underestimation of fallout from the tests.’

I had a smile.

Carmyl Winkler

July 2024

RSS Feed

RSS Feed